Hospitals urge ways to cut $1 trillion administrative cost

Included in the hospitals' requests were reductions in some of the 1,700 quality measures collected by CMS.

Hospital advocates have submitted a range of regulatory changes to the Trump administration that they say could cut the estimated $1 trillion annual cost of health administrative requirements.

The suggestions followed an April 11 request for information on needed deregulatory actions from the Office of Management and Budget. Previous research has estimated administrative costs consume 13% to 24.5% of national health spending and more than $1 trillion annually.

The OMB request followed an April 9 executive order that directed departments and agencies to identify unlawful regulations in accordance with a list of 10 Supreme Court decisions made since 2015. The deregulatory push could help the administration achieve a goal to cut 10 regulations for every new one promulgated.

The American Hospital Association (AHA) submitted a list of 100 specific policy changes or broad areas where changes are needed.

“Addressing unnecessary administrative burdens and costs would go a long way to not only lower health system costs but support the accessibility of care,” said the letter from Rick Pollack, president and CEO of AHA. “Many hospitals are financially unstable, with nearly 40% operating with negative margins. This has led to closures of services and even entire hospitals, and the resulting loss in access to care is felt by entire communities.”

The list comes, in part, from 2,700 member-hospital surveys.

“Enacting even half of them would make a real difference throughout the health care system,” Pollack wrote.

The wide-ranging AHA list focused on deregulatory suggestions in billing and payment, quality and patient safety, telehealth and workforce requirements. It included existing federal healthcare regulations and initiatives in Medicare, Medicaid, Medicare Advantage and marketplace plans and across multiple federal departments and agencies. Some changes sought would apply to all payers.

Among the policies or programs AHA sought to end were:

- The “information blocking” rule from the 21st Century Cures Act

- The two-midnight inpatient rule

- Increasing Organ Transplant Access Model, a new mandatory payment model

- All mandatory models, including the Transforming Episode Accountability Model

- Hospital Readmission Reduction Program

- 42 Code of Federal Regulations Part 2 requirements providing special privacy protections for behavioral health patients

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) rule that allows union representatives to accompany OSHA inspectors

- Originating site restrictions on telehealth

- Federal Trade Commission’s Non-Compete Clause Rule

- Independent dispute resolution process

AHA also urged new initiatives, such as capping non-economic and punitive damages as part of medical liability and shifting cost-sharing collection responsibilities to payers.

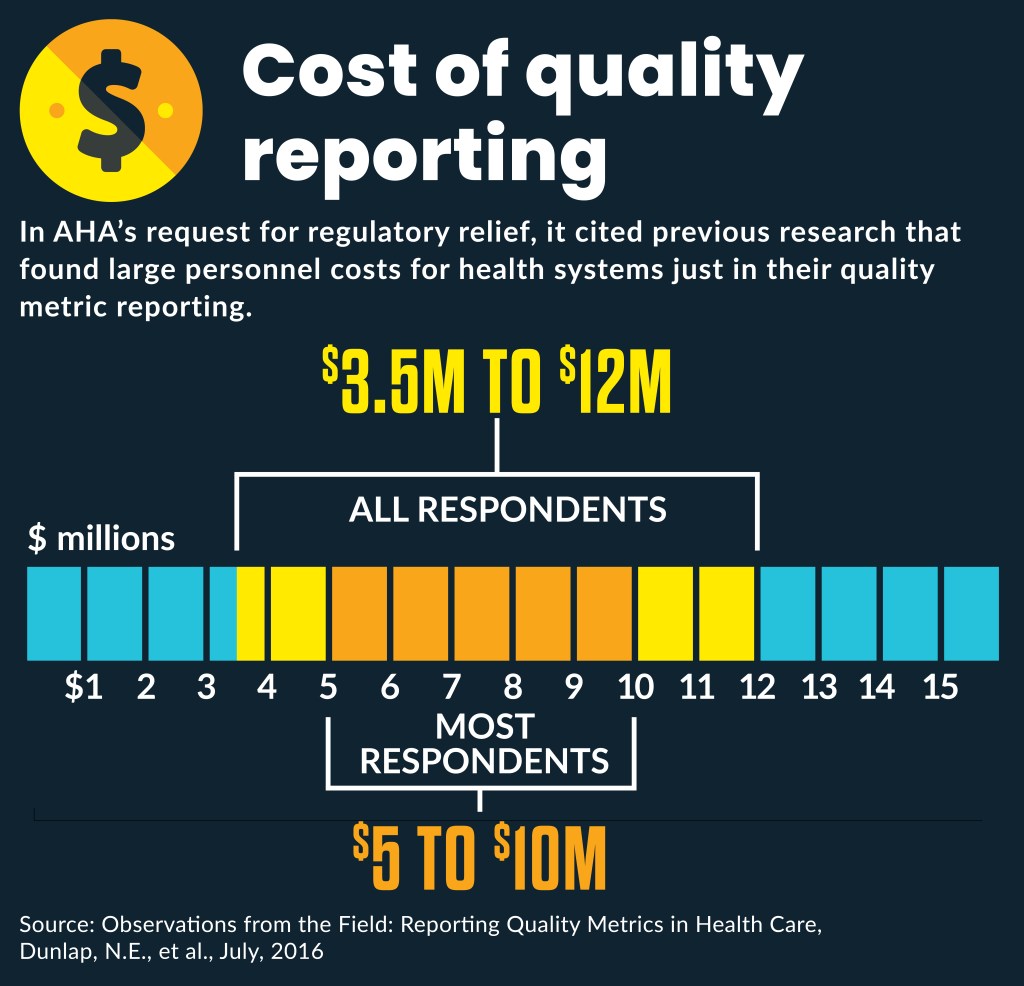

Quality reporting

A big focus of hospitals’ deregulatory push is scaling back quality measures. More than 1,700 quality measures collected just by CMS, according to A 2019 report from McKinsey & Company.

The Federation of American Hospitals (FAH) urged eliminating a range of quality reporting measures in several programs.

For instance, FAH said a range of measures in the hospital inpatient quality reporting and value-based purchasing programs were initially intended to incentivize quality infrastructure but “these measures now impose a significant reporting burden with little utility for hospital performance differentiation.”

Conditions of participation

The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) urged modifications to obstetrical service standards and other maternal conditions of participation (CoP) finalized in a November 2024 rule. Without changes, the requirements could cause more hospitals, especially rural critical access hospitals, to eliminate such services.

From 2010 to 2022, 537 hospitals eliminated obstetric services, including 299 in urban areas and 238 in rural communities, according to a 2024 JAMA study.

The new CoP requires Medicare and Medicaid participating hospitals and critical access hospitals that offer obstetrical services to implement several changes related to service organization, staffing, delivery of services and training.

“If hospitals feel they are not adequately equipped to meet these standards or that additional investments must be made to meet these requirements, providers struggling to operate these services may ultimately make the decision to eliminate these services to avoid significant penalties for failure to meet CoP requirements,” wrote AAMC.