James Mathews: Why the future of U.S. healthcare depends on Medicare and CMS

As the Medicare program approaches beneficiary age, it is worth taking stock of current and near-term events in Washington that will have potentially profound implications for the program’s future. In particular, it is important to acknowledge CMS’s pivotal role as the agent of the positive changes in ensuring Medicare’s continual service to the elderly and disabled populations.

To fully appreciate Medicare’s importance and CMS’s role, one must understand how the Medicare program has grown and all that it has accomplished since its inception.

From baby steps to giant strides

On July 30, 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Social Security Amendments of 1965, which established the Medicare program, the Federal government’s health insurance program for the elderly.a By the summer of 1966, 19 million Americans had enrolled in Medicare (including former President Harry Truman and his wife Bess, Medicare beneficiaries 1 and 2, respectively). Early spending figures approached $5 billion annually in the first full years of program operations (starting at $4.2 billion in 1967).

Fast forward to 2023, at which point Medicare expenditures exceeded $1 trillion, reflecting coverage of about 66 million Medicare beneficiaries — nearly 20% of the U.S. population.

The nation has seen tremendous improvements in demographic characteristics of the Medicare-eligible population since Medicare’s creation, which the program arguably has played a role in promoting. Average life expectancy at birth for the nation overall increased from about 70.3 years in 1965 to 79 years in 2025, and life expectancy for the age 65 and over population increased from roughly 14.6 years to 18.8 years over this same period.b In 1966, 28.5% of Americans aged 65 and over had incomes at or below the poverty rate; by 2023, that share had fallen to 9.7%.c The fact that Medicare provides near universal coverage for the population over age 65 (3% of the elderly population were without insurance in any given year for the past decade) has certainly contributed to these positive trends.

Room for improvement is a universal concept

Like every other governmental program, CMS is not immune to criticism. Its predecessor, the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA) was all too easy to disparage as a moribund bureaucracy isolated in the western suburbs of Baltimore. During my own tenure starting with HCFA and moving on to CMS, the “80/20 rule” was axiomatic — 80% of the work was done by 20% of the staff.

Moreover, anyone who has had any interaction with CMS — as a stakeholder, overseer, employer or beneficiary — could easily find cause for criticism. But bureaucracies are easy targets, and it can be instinctual to pile on and overlook the far-greater value that they can deliver, despite unavoidable shortcomings.

While the zeal with which Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) has sought to root out purported waste, fraud and abuse across the federal government is commendable (putting aside commentary on its execution), it is worth taking a moment when pursuing such actions to consider CMS’s mission and the resources it has historically been given to perform its assigned duties.

What CMS continues to do

In addition to serving Medicare’s 66 million beneficiaries, with $1 trillion in federal spending — a daunting responsibility by itself — CMS also has responsibility for the federal aspects of the Medicaid program and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), which together cover roughly 80 million Americans, at a Federal cost of over $600 billion in benefit spending (FY23).d Putting aside its required interactions with other federal health insurance programs and coordination with nonfederal insurance, CMS is directly responsible for the health insurance coverage of just over 40% of the U.S. population, with benefit payments for these covered lives representing a quarter of overall federal spending in FY24.

Given the magnitude of CMS’s responsibilities, what most stakeholders don’t readily grasp about the agency is the relatively — some may say impossibly — low cost it incurs in administering its programs. In FY24, CMS requested a discretionary appropriation of $4.5 billion for “program management” activities, including operations and federal administration costs, and in its budget request, CMS anticipated that this funding would cover just over 4,300 full-time-equivalent (FTE) employees.e

To scale these numbers, CMS’s program management budget represents less than one-third of 1% of total benefit spending, or about 0.07% of the total federal budget.f Further, this level of efficiency is not anomalous: In FY98, when CMS was charged with implementing hundreds of discrete provisions of the Balanced Budget Act of 1997, its administrative budget was $2 billion, covering just over 3,900 FTEs, to administer roughly $380 billion in benefit payments. If anything, CMS has become more efficient over time.

How CMS can continue to do more

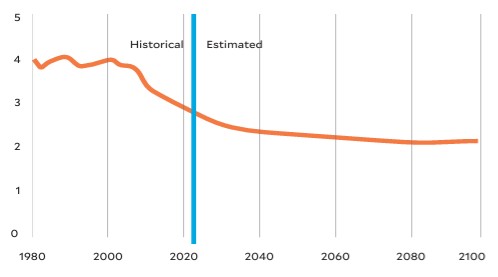

Despite this achievement, CMS will come under increasing pressure to do more with less. The ratio of workers paying Medicare taxes to each Medicare (Part A) beneficiary has declined from 4.0 in 1980 to 2.8 in 2023, and it will continue to drop before leveling off around 2070 (see the exhibit below).g The reduction in payroll-based sources of funding (payroll taxes for the Hospital Insurance trust fund and general revenues for Supplemental Medical Insurance ), coupled with the gradual increase in enrollment through 2034 as the baby boomers continue to age into the Medicare program, will make it imperative for the program to leverage new efficiencies at every opportunity.

Historical and projected numbers of workers per

Medicare (Part A) beneficiary, 1980-2100

Medical Insurance trust funds, Figure III.B.4, letter of transmittal, May 6, 2024

But further efficiencies are within reach only if CMS is adequately resourced to face these impending challenges. The following steps are needed to ensure that the agency can be responsive to the needs of a growing Medicare population (and of the providers who serve this population).

1 CMS must be adequately staffed. In Herman Wouk’s The Caine Mutiny, Ensign Thomas Keefer describes the U.S. Navy as “a master plan designed by geniuses for execution by idiots.” That’s not CMS. After 50 years of legislative changes ranging from annual tinkering to substantial foundational overhauls (including the Balanced Budget Act of 1997, the Affordable Care Act of 2010 and the Inflation Reduction Act of 2021), Medicare has become incredibly complex both in scope and depth. It requires staff who have not only a deep understanding of current policy but also the ability to plan for future program needs. The fact that the ostensible 2026 HHS budget pass-back document that was circulated in April did not indicate substantial changes to CMS funding or staffing is a good early sign that the Trump administration recognizes the need for stability at CMS. But policymakers would do well to strategically think about and plan for future program staffing needs.

2 CMS’s IT infrastructure must be adequately resourced and supported. The agency produces, maintains and analyzes an unfathomable and ever-increasing amount of information, which is not only necessary for myriad operational purposes (operations, policy development and analysis, program integrity), but also includes extremely sensitive health and personally identifiable information on 40% of Americans. Yet CMS continues to rely on legacy systems and programming languages dating back to the 1960s. Efforts to transition from these systems have been ongoing since at least 2013 but are not yet complete. As threats to information security multiply, it is imperative that CMS be given the resources to modernize its IT infrastructure.

3 CMS must assume a more active role in managing change. Over the past decade, Medicare beneficiaries have elected to receive their benefits not through the traditional fee-for-service program, but through Medicare Advantage (MA, or Medicare Part C), where private managed care plans are responsible for delivering benefits (including supplemental benefits not covered by traditional Medicare). Currently, 54% of eligible Medicare beneficiaries are enrolled in MA. My predecessor in this column, the esteemed Gail Wilensky, PhD, was a tireless proponent of Medicare managed care, arguing that such plans could theoretically provide better, more integrated care to Medicare beneficiaries at a lower cost than the traditional program.

Unfortunately, there is little evidence this potential has been effectively realized in the MA program, in part due to the irresistible financial incentives Medicare creates for MA plans, and in part because CMS’s interactions with plans have been over-cautious, based on its desire to avoid running afoul of the “non-interference” clause of the Medicare statute establishing MA. Such a hands-off approach will need to change going forward, and CMS will need to more actively manage the care managers, if MA is to fully realize the potential that guided its incubation in Medicare.

CMS only needs effective resources to succeed

CMS has perhaps done an imperfect job as the chief steward of the Medicare program during its first 60 years. But one can argue that it is impressive that it has done the job at all, given the constraints it has toiled under.

Most important, Medicare and the other programs CMS administers represent an enduring social contract between the government and the program’s stakeholders. And to deliver on that contract for the next 60 years, CMS must only receive the resources necessary to move

forward effectively.

Footnotes

a. Medicare’s origins can be traced to legislation developed and introduced more than two decades earlier, the Wagner-Murray-Dingell Bill of 1943, which would have created a taxpayer- and employer-funded national health insurance system for all Americans.

b. Social Security Administration, “Table V.A3. period life expectancies 1, calendar years 2002-2080, intermediate cost assumptions,” page accessed on April 30, 2025.

c. Shrider, E.A., Poverty in the United States: 2023, U.S. Census Bureau, Sept. 10, 2024.

d. CMS, “November 2024: Medicaid and CHIP eligibility operations and enrollment snapshot,” March 28, 2025; and Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, MACStats: Medicaid and CHIP data book, December 2024.

e. HHS and CMS, Justification of estimates for appropriations committees, fiscal year 2024.

f. These numbers do not include certain contractor and fee-funded positions. Medicare administrative contractors are responsible for the vast majority of Medicare’s claims-processing workload.

g. The 2024 annual report of the Boards of Trustees of the Federal Hospital Insurance and Federal Supplementary Medical Insurance trust funds, letter of transmittal, May 6, 2024.