GLP-1 drugs present an uncertain opportunity for healthcare and the nation

Bariatric surgery volume has taken a hit, but some experts speculate a rebound is possible.

The wave of weight-loss drugs being prescribed to patients across the country may be behind a new era in obesity treatment. The drugs not only could be an appropriate treatment for millions of Americans but also could disrupt the industry’s existing bariatric surgery efforts and have other far-reaching consequences.

The soaring demand for GLP-1 drugs, shorthand for glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists, may be shifting attitudes about what it means to be overweight, experts say.

“These (drugs) are a game-changer in medicine,” said Marc Bessler, MD, chair of surgery at Lenox Hill Hospital, part of the Northwell Health system in New York. Because GLP-1 treatments are drug-based, obesity is coming to be seen as the disease that it is, he said.

“Before we had anything effective other than surgery, people saw it as a failing,” he said. “When there’s a medication to treat something, it usually means it’s a disorder or disease, and I think people are starting to see it as such,” Bessler said.

The early impact of GLP-1 drugs for weight loss has hit the surgery suite hard. The number of bariatric surgeries fell 8.7% in the last six months of 2023 compared with the same period in 2022 while the number of patients prescribed GLP-1 drugs rose 105.7% in the same time frame, according to a study in JAMA.a

Those trends give reason to believe GLP-1 drug costs will fall and insurance coverage will rise. Even so, the speed and scope of the drugs’ influence on healthcare remains a huge unknown.

Meanwhile, tempering demand for these medications is the fact that they are not effective for many of the people who take them. A recent study of a clinical trial of 483 adults found that nearly 18% did not respond to the drugs.b

And some of those who do lose weight with the drugs give them up because of side effects or not wanting to take the drugs indefinitely to maintain weight loss.

Thus, GLP-1 drugs present both an opportunity and a challenge for health systems — and their leaders should actively consider how they will respond.

“This is an environment that’s not going to be going away anytime soon,” said Nicole Faucher, president of Clearway Health, a Boston Medical Center subsidiary that supports specialty pharmacies. “So [systems] need to take an active participation or they will, I think, lose some patients to other systems or outside entities.”

The workforce challenges

The first task in responding to the impact of GLP drugs is training, organizing and aligning the workforce to accommodate the major disruption coming their way, given the demographics of patients and their weight. More than 42% of U.S. adults over age 20 meet the criteria for obesity, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. To meet that demand requires new staffing approaches.

“It can’t be just simply [patients] keep showing up at primary care offices,” Faucher said. “We know it’s almost impossible to get appointments sometimes,” she said.

To meet this demand, some health systems have created weight-management clinics that have medical oversight from the health system but are staffed by mid-level providers or pharmacists.

“That’s one of the models that we find works very successfully,” Faucher said.

Emily Fitt, a consultant with Sg2, a Vizient company, regards the weight-management clinic concept as promising, but she thinks such clinics should target the highest-acuity patients.

“When we are talking about millions upon millions of Americans [who] could technically qualify for these medications, a weight-management clinic is not going to be scalable,” she said. “So how do we engage or revamp our primary care workforce to include more obesity training for primary care physicians to really manage this population?”

A drug by any other name …

Semaglutide, one of the top-selling drugs in the United States in 2024, is marketed as Wegovy for weight management, as Rybelsus in an oral formulation for managing Type 2 diabetes and as Ozempic for treating Type 2 diabetes, reducing cardiovascular risk in patients with Type 2 diabetes and reducing the risk of kidney disease worsening in adults with Type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease.

More than half of all U.S. adults — nearly 137 million individuals — met the criteria for one of the uses for semaglutide approved by the FDA, according to an analysis published in JAMA Cardiology.a Two other drugs, liraglutude and tirzepatide, are approved for weight loss under the respective brand names of Saxenda and Zepbound.

a. Shi, I., et al., “Semaglutide eligibility across all current indications for US adults,” JAMA Cardiology, Nov. 18, 2024

Management skills needed

Effective management of patients receiving GLP-1 therapy is key to mitigating a well-known problem: side effects that prompt many patients to discontinue GLP-1 drugs before they achieve the full benefits.

“We need more support around our clinicians who are providing treatments,” said Jamy Ard, MD, past president of The Obesity Society and co-director of Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist Weight Management Center.

Ard believes obesity treatment with GLP-1 drugs requires a level of wrap-around care similar to that used for metabolic and bariatric surgery — six months of preparation before surgery and potentially years of follow-up care, including support from nutritionists, exercise physiologists and behavioral health providers. Although GLP-1 drugs lead to weight loss approaching the average weight loss from metabolic and bariatric surgery, Ard noted that there is “very little of that support to help mitigate any of the potential adverse events.”

Many physicians who are prescribing GLP-1 drugs for weight loss have no training in obesity management. Speaking at a recent National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine webinar, Ard said knowing how to slowly titrate the dosage of GLP-1 drugs and knowing when to switch to a different medication can help patients stay the course.

GLP-1 drugs’ cost effectiveness

David Kim, PhD, a University of Chicago health economist, advocates for a multifaceted approach to weight management. At their current prices, GLP-1 drugs are not cost-effective for weight loss (see sidebar at right).

In a recent article, Kim and colleagues demonstrated how a hybrid strategy — GLP-1 for initial weight loss, followed by an alternative approach to weight maintenance — would be a more cost-effective approach to addressing the obesity epidemic.c The alternative approach they examined was behavioral interventions, nutritional support and a lower-cost medication regimen.

“You start with the GLP-1 so that you can achieve the maximum weight loss, then because the price is too high to pay for the weight maintenance, you can switch off to less-effective but much more cost-saving strategies,” Kim said. “Our argument is that’s better for society.”

GLP-1s? Are they worth the price?

Popular GLP-1 drugs approved for weight loss cost more than they are worth, said David Kim, PhD, a health economist at University of Chicago.

“There are a lot of clinical benefits that GLP-1s can confer, but if you’re just looking at whether GLP-1s have a good value, then my research is showing ‘no’ at the current price,” he said.

Consider that the list prices of a year’s supply of approved GLP-1s exceed:

- $11,000 for Ozempic, the formulation of semaglutide approved for Type 2 diabetes

- $16,000 for Wegovy, the formulation approved as a weight-loss treatment

- $12,000 for Mounjaro and Zepbound, the formulations of tirzepatide approved for Type 2 diabetes and for weight loss, respectively

Manufacturers’ savings programs and pharmacy discounts may reduce those prices. But Kim found that, if patients need to be on GLP-1 drugs indefinitely to achieve and maintain weight loss, their expense outweighs the economic benefit of avoiding obesity-related problems.

Using a standard methodology to evaluate cost-effectiveness, Kim and his colleagues found that one-year of tirzepatide for weight loss should cost about $4,500; for semaglutide, $3,400.

Kim’s analysis was done before the FDA approved GLP-1 drugs for chronic kidney disease, potentially sparing people from progressing to end-stage renal disease. Thus, Emily Fitt, a consultant with Sg2, a Vizient company, believes the drugs will soon be cost-effective.

“That could prevent somebody from utilizing dialysis,” she said.

What GLP-1 drugs mean for bariatric surgery

At Lenox Hill Hospital, Bessler and his colleagues perform about 500 bariatric surgeries a year at a contribution margin of $10,000-$12,000 each. Only about 2% of individuals whose weight makes them eligible for surgery have chosen that treatment. Bessler thinks some hospitals may see an increase in bariatric surgery as individuals — and clinicians — come to accept obesity as a treatable disease rather than a failure of willpower.

“[Such] surgery might have a little blip as people look at this because 98% of patients haven’t been effectively treated,” Bessler said. “Now that we recognize meds are available, how do we break this down into different groups who will benefit from different treatments?”

In its national forecast for the decade ahead, consulting firm Sg2 estimates the number of bariatric surgeries will fall by about 15%. Meanwhile, Sg2’s parent company, Vizient, predicts that two GLP-1 drugs — semaglutide and tirzepatide — will be among the top 10 biggest-selling drugs in the year that starts July 1, 2025.

Rather than seeing surgery versus GLP-1 drugs as a battle, Fitt thinks health systems should operate them in tandem.

“We are seeing the modalities be used together in some scenarios,” she said. “We have these different tools that work for different patients.”

Fitt thinks an integrated approach is key to bariatric surgery programs moving forward.

“If patients need to go from a GLP-1 to bariatric surgery, how do we make that switch as seamless as possible?” she said.

Terry Scarborough, MD, a surgeon at Texas Laparoscopic Consultants, agrees.

“We use GLP-1 medicines for people that have already had bariatric surgery too,” Scarborough said. “If they’re having weight regain or if they want to lose a little bit more, we use it for post-op patients.”

“Some [patients] that had stopped the process to take the GLP-1s are coming back for surgery,” Scarborough said.”

“I don’t think bariatric surgery is going to disappear anytime soon.”

Footnotes

a. Schweitzer, K., “What does the rise of GLP-1 drugs mean for bariatric surgery?” JAMA, Jan. 31, 2025.

b. Squire, P., et al., “Factors associated with weight loss response to GLP-1 analogues for obesity treatment: a retrospective cohort analysis,” BMJ Open, Jan. 15, 2024.

c. Kim, D., Hwang, J.F.H., and Fendrick, A.M., “Balancing innovation and affordability in anti-obesity medications: the role of an alternative weight-maintenance program,” Health Affairs Scholar, May 2, 2024.

For more discussion of GLP-1 drugs, read “Despite positive outcomes, coverage of GLP-1 drugs presents complicated questions,” by HFMA senior editor Nick Hut.

Payers not eager to pay

As of Jan. 1, Kaiser Permanente tightened its payment policy for glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor antagonists (GLP-1) for weight loss. The drugs are now covered only for patients with a body mass index over 40. Independence Blue Cross, the biggest health insurer in the Philadelphia market, stopped covering GLP-1 for weight loss entirely, and so did Allina Health, a 12-hospital system based in Minneapolis.

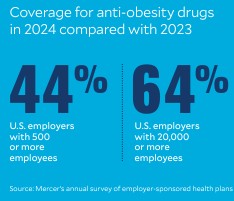

Coverage for anti-obesity drugs rose in 2024 — 44% of U.S. employers with 500 or more employees and 64% of employers with 20,000 or more workers cover them — compared with 2023, according to Mercer’s annual survey of employer-sponsored health plans. But throughout the year, many insurers and employers said they would start restricting or eliminating GLP-1 coverage of drugs for weight loss, while retaining coverage if patients have Type 2 diabetes.

David Kim, PhD, a University of Chicago health economist, expects insurers to be wary as long as the prices remain high. Regardless of their effectiveness, the GLP-1 issue has a unique level of unaffordability caused by the following factors.

1 Population size. Many insurers cover treatment for Duchenne muscular dystrophy, which can top $1 million a year, but there are fewer than 50,000 patients with the disease in the United States, according to Pfizer, and not all are candidates for the treatment. By contrast, Beth Israel Deaconness Medical Center researchers have estimated that 129 million Americans could be eligible for semaglutide, the most popular GLP-1, for weight loss alone.

2 Popularity of the new weight-loss drugs. “Patient demand is also very big,” Kim said. “So (insurers) know that they’re going to take it.

3 Ongoing treatment. Unlike some other high-cost drugs — for example, $84,000 treatment for hepatitis C that saved thousands of lives by curing the disease — GLP-1 medications in general are effective only as long as patients continue to take them.

“These factors are affecting payers’ hesitations — ‘How are we going to pay for this?’ — even though [they know] all the great things that GLP-1s offer,” Kim said.